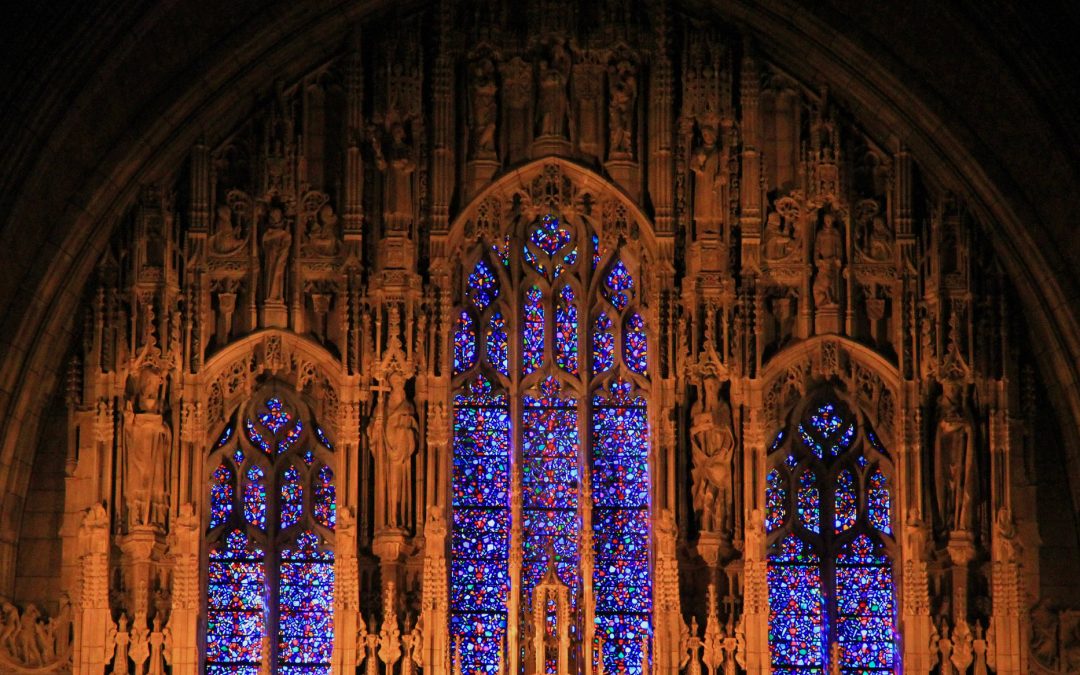

My son, Henry, was baptized a little over five years ago in a particularly grand church in New York City, St Thomas Fifth Avenue. The church is located one of the busiest streets in Manhattan. Its towering Gothic arches and open doors bring in hundreds of thousands of accidental pilgrims every year.

The day that Henry was baptized there was one such unexpected visitor: it was, of all people, Bono, the singer of the legendary rock band, U2. I’ll admit to the fact, whether it’s cool or not in 2019, that I am a huge U2 fan. So, I was basically freaking out! I said to myself, “If he’s still here at the end of mass I’m taking Henry up for a blessing!” And to my astonishment he was, and I did.

I walked straight up to Bono—wearing his signature glasses even inside the darkened church—and told him that my son was to be baptized that day and asked if he might give him a little blessing.

He was wonderfully kind and took Henry into his arms, almost completely ignoring me, and rubbed his face sweetly against little Henry’s head. And after what, to my memory, became an almost awkward amount of time of head rubbing, he said these words to me: “You must raise him to do great things in this world. There’s so much to do. So much to do.”

What a profoundly “Bono” sentiment, I thought. And quite beautiful.

Before I turn the tables on my dear hero Bono, I’d like to affirm what’s true in his statement. There is much to do. In our gospel lesson today we meet a self-made man; a man who might, in our day, grace the covers of esteemed financial magazines. A man who had become so rich that he didn’t know what to do with all his possessions.

But instead of recognizing his common humanity with the less fortunate ‘other,’ and using what he had been blessed with to bless them as well, he built bigger storehouses for all his wealth so that that he could keep it all to himself. So that he could, “relax, eat, drink, and be merry,” as the gospel says.

In his mind, he probably saw himself as “successful” and deserving of all the wealth he had accumulated. But God calls him a frightening thing. He says, “You fool! This very night your life is being demanded of you.” In failing to recognize his place in a common humanity this man was lost to himself. He was, as God says, a fool. A man as good as dead, even before he died.

In the same way, it’s easy for us to ignore the humanity of the refugee at our border or the poor in our midst. Just yesterday there were two more horrific mass shootings. And these can easily become simply political issues, obscuring their underlying humanity.

So, there is much to do. And our inaction can be damning. But the core of the problem lies deeper than just what we do or fail to do. It is an issue of how we perceive who we are.

I want to speak now a bit on “identity” and connect it back to the incredibly rich epistle reading that we just heard. There’s much talk today about the subject of identity and no shortage of controversy and confusion.

This weekend we are surrounded by those who identify as “musicians.” I happen to be one of these such persons. As is blessed uncle Bono. Music is something that I have done for many years and it has undoubtedly become a part of who I am. But if I am honest, my identity as a musician, as accurate as it may be, surely does not reveal the inward depths of who I am.

The day that my son met Bono he was about to undergo a somewhat frightening ritual of “identification.” And despite Bono’s very “Bonoesque” pronouncements, it would have nothing to do with what he does or doesn’t do in his life.

Many people find baptisms cute and heartwarming, but I’d like to focus on their strangeness. That day at St Thomas, we the Church, said to a tiny baby, after ritually drowning him, “You have died, and your life is hidden with Christ in God!” Please let the profound strangeness of this action set in.

In the Western Church, the outward ritual of baptism is usually quite restrained—pouring water gently over the head, with a shell or something quite delicate like that. But maybe you’ve seen the viral video of a Romanian priest baptizing a baby. In the video, the baby is naked and being flipped over, somewhat violently, and fully immersed in a giant font, all while he has a look of horror on his tiny face, three full times. It’s certainly not cute or nice. It’s honestly a bit frightening.

But in some ways, it’s closer to what the Church intends in baptism. This severe action pronounces an identity on a baby who is completely unaware of it and incapable to resist. This is certainly at odds with our modern insistence on autonomy and our cultural veneration of the self-made man. But it says something essential to our Christian understanding of identity.

To be a Christian is not to say that the self or the individual doesn’t exist—we are not interested, as some religious traditions are, in the annihilation of the self or becoming a drop in the ocean of the universe—but it is to say that we are not finally self-determined. That what we do or don’t do fails to get to the bottom of who we truly are.

To be a Christian is, instead, to submit to a strange and beautiful reality—that God has, in the incarnation of Jesus Christ, forever identified himself with humanity. To be a Christian is to identify with the God who has identified with us. And to identify in such a way that we can no longer see ourselves as finally separated or wholly distinct from each other, or from Christ.

Our protest against injustice then is not simply that individual rights are being violated, but that what is happening to “them” cannot finally be separated from “us” and, even more profoundly, from Christ. We must remember the words of Our Lord in Matthew’s gospel, “Just as you did it to one of the least of these, you did it to me.”

It is not just a matter of “doing some good,” or “paying it forward” in hopes of some future reward, but of acknowledging the significance of the fact that our humanity has been consecrated to God in the incarnation. Whatever good we do is centered on the fact that Our Lord has forever taken on our nature and united himself with our humanity in such a way that to look at another human is to see an icon, a living image, of the invisible God.

The theologian Karl Rahner writes that because of this reality, “The grace of God no longer comes down from on high, from a God absolutely transcending the world, and in a manner that is without history.” Instead, “[God’s grace] is permanently in the world in a tangible historical form, established in the flesh of Christ as a part of the world, of humanity and its very own history.”

And it is the Church, the body of Christ, which mediates this gracious reality. Through her we receive our identity: we receive the Holy Spirit and are marked as Christ’s own forever. Through her we are fed with Christ’s own body and blood. And as St Augustine notes, we become what we receive. We are Christ’s body. And this is not simply a nice metaphor; it is surely a mystery, but it is much more than a metaphor.

When Henry was baptized, our beloved rector, Father Mead, said something that, despite not coming from the hallowed lips of my hero, Bono, has stuck with me just the same. He said, “Little Henry will spend the rest of his life living into the reality of what has just happened.” This is the same with all of us. We fail to live into the strange reality that God has become man in Palestine. We fail to live into the wonderful reality that in our baptism we are made members of Christ’s body. We fail to see each other as icons of Christ, of God. But that does not change who we are. Even when we are lost to ourselves, we are not lost to God. For he is the final identifier.

This is what God’s grace does. It brings together the mess and contradiction of our lives and names it. And places it within a body that is Christ’s. A body that is ours, but not exclusively. “For you are dead and your life is hidden with Christ in God.”

I’m going to end with a quote from one of my favorite theologians, Rowan Williams. It’s rich, so bear with me. I promise it’s worth it.

He writes, “Jesus is for us the Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end of all things, because there is no place where the icon of that suffering face cannot be unveiled and worshiped. For him there are no divisions, no parties, no exclusivities of race or sex or achievement of power: he is there for all, because he has made himself God’s “space,” God’s room in the world … He is unprotected; no walls, no gravestone even, can seal him in.

God and humanity are knotted together there in that space of history, those short years in Palestine, so that that history is the sign that interprets all history. And by that death all death is conquered.”

For, as St Paul tells us in today’s epistle, “Christ is all in all.”

Adapted from the sermon. Audio available here.